We’re in These Streets! Byrd Barr Place’s Reopening

United Way of King County is out and about in your community! We’re keeping an eye and a pulse on happenings, events, organizations and activities throughout King County as work toward a racially just community where all people have homes, students graduate and families are financially stable.

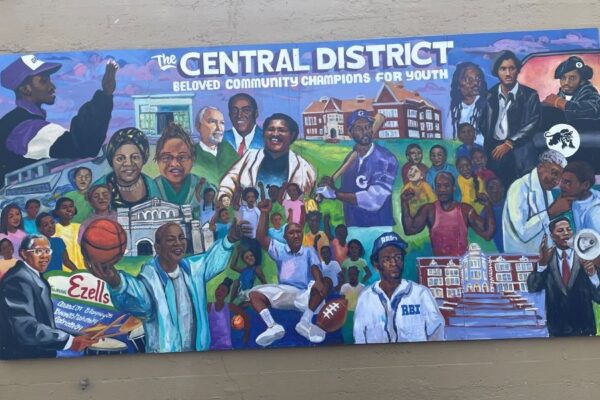

We’re in These Streets is an occasional blog post that highlights your community. Today, we highlight Byrd Barr Place, a social services organization in Seattle’s Central District. Byrd Barr Place is part of the Black Community Building Collective, a group of 15 Black nonprofit groups who help determine how United Way funding can support equitable recovery and long-term viability of King County’s Black community.

Since the 1960s, Byrd Barr Place has been synonymous with the old fire station in Seattle’s Central District, as people near and far have flocked to the location for support and services. The organization is known for providing food, shelter, utility assistance and financial tools while advocating on behalf of those they serve by petitioning lawmakers for just and equitable policies.

But until recently, Byrd Barr Place was merely a tenant in its confines, 116-year-old Fire Station No. 23—which is on the National Register of Historic Places. Then in October 2020, after 10 years of negotiations, the City of Seattle transferred ownership of the building to Byrd Barr Place.

But only ownership was granted: Byrd Barr Place was responsible for its upkeep and maintenance, with no financial assistance from the city.

That led to a $12.8 million renovation campaign in less than a year, fueled by the group’s determination to embrace its new ownership. What began initially as an effort to ensure the centuries-old structure was earthquake proof has become a complete modernization of the interior. While the Byrd Barr Place staff worked from home during the pandemic, its offices got what director Andrea Caupain called a “hospitality upgrade.”

“When the building designer first met with us, we said that we’re not going for the typical social service agency look. We’re going for the plastic surgery waiting room look,” said Caupain.

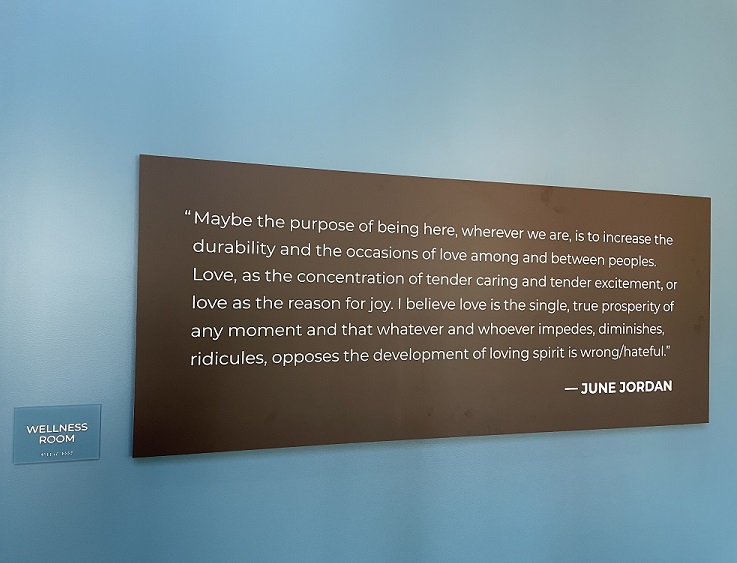

The 15,000-square-foot structure has kept its brick façade, but Byrd Barr did masonry and roof repairs. For earthquake safety, there were 27 tons of steel added. The staircases have been modernized. For ADA compliance, doorways and hallways were widened and an elevator was installed. Byrd Barr Place also added expansive meeting room space and a wellness room for those who breastfeed and administer diabetes medication.

Caupain said that they raised funding for the renovation “by leaving no stone unturned.” The organization received $3 million in state and local funding, $3.2 in tax credits and the rest from private philanthropy.

Caupain says the effort was worth it after gaining outright ownership—a rarity among nonprofit organizations of color. “We now have dominion over our space at a time where Black people still have not experienced what it’s like to have dominion,” said Caupain.

Though its confines are different, its mission and goals are unchanged: both service and systems change work.

“We help people meet immediate needs for food, shelter and utility assistance,” said Caupain, who added that such basic needs have been amplified during a season of skyrocketing inflation.

“People don’t realize but utility assistance is quite an interesting thing for poor people,” Caupain added. “If you’re in shut off, you can’t heat your house. You can’t cook. There are basic things you can’t do with your life. People who are threatened with shutoff from [the] utility company, we help to broker and negotiate so they keep their power and lights and heat on. We have now recently extended that to AC in the summer because there is warming and our summers are longer and hotter. We provide air conditioners for people.”

Caupain said the organization’s experience with the people it serves inform its social and racial justice work.

“We have [a] community engagement arm where we do policy and system change work,” Caupain said. “We gather data on Black Washingtonians, we push that data out to our sibling Black organizations and we share that data with policy makers and philanthropists who are in spaces where decisions are being made on behalf of Black people.”

Comments