Tackling Food Insecurity in King County’s Indigenous Communities

This week, United Way of King County launched a fundraising effort to provide food for neighbors in need. We are also highlighting grantees whose work includes providing food for their communities.

Here we feature Chief Seattle Club, a Pioneer Square-based, Indigenous housing and human services agency.

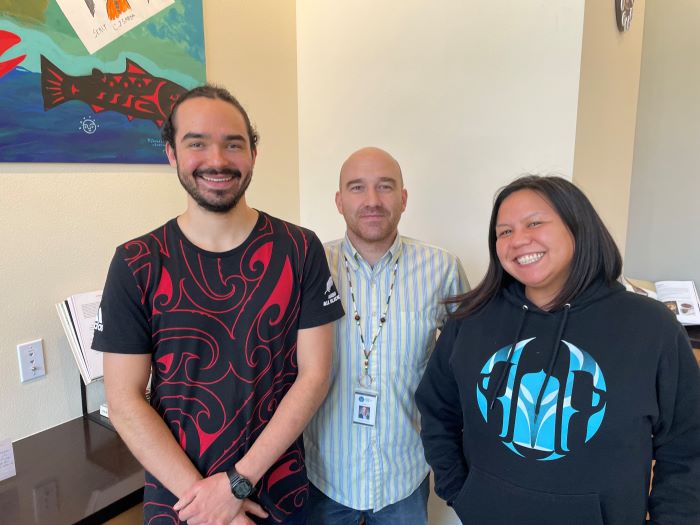

We chatted with Chief Seattle Club director of development James Lovell (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe) to learn more about the organization’s work to combat food insecurity.

United Way of King County: What are the origins of the Chief Seattle Club and what is its primary focus?

James Lovell: In the 1950s and 1960s, the goal of the federal government was to eliminate tribes as something they had to manage. The previous 500 years of genocide hadn’t done the trick. We kept surviving. So, they established a policy where if they could just eliminate us as a racial category that would finish the job. They made a bunch of incentives for folks to leave the reservations and come to the cities. Folks came to the cities and all those [incentives] disappeared, all the education promises, the housing, the social services—there was no safety net. A lot of folks were able to make their way, different parts of the community came together, and that’s when the Seattle Indian Health Board was founded in 1970, United Indians of All Tribes was founded in 1970, and that’s when Chief Seattle Club was founded.

United Way of King County: Who does Chief Seattle Club serve?

James Lovell: Chief Seattle Club wasn’t so much this group where people had found their way together; it was folks for whom the system were still failing and they were living on the street. Chief Seattle Club began as an organization working with all our Native community folks who were unsheltered, handing out sandwiches from the back of a van. Over time, the program grew and services grew and finally, in the early 2000s, we bought the Day Center next door, our first building.

The Day Center is what it sounds like—a day shelter. It opens at 7 a.m. and closes at 2 p.m. We don’t have overnight facilities there. Folks who were staying on the street would come in at 7 in the morning, get warmed up, get breakfast, get showered, get hygiene supplies and use laundry services. We are the permanent mailing address for hundreds of folks. But the real core of basic needs stuff, especially around meals, was right there, too. And we still have our kitchen.

United Way of King County: And now you have permanent supportive housing as well. How did that come about?

James Lovell: We were doing so much social service, healing and recovery work in the Day Center, but we knew that folks had to be ready to go back on the streets at 2 p.m., because that’s what we had the capacity to do. Our previous executive director [Colleen Echohawk] and our current executive director [Derrick Belgarde] were the leaders in saying, “Enough is enough. No one [is] housing our people well.” Using the Lushootseed word for “home,” which is ʔálʔal [pronounced “all-all”], we established this building that has 80 units of permanent supportive housing. ʔálʔal opened in January of 2022. And we have the ʔálʔal Café, an externally facing part of the Chief Seattle Club.

United Way of King County: The USDA’s definition of a food desert is as follows: a tract of land comprising at least 100 households located more than one-half mile from the nearest supermarket and without vehicle access. Are Chief Seattle Club and ʔálʔal located in a food desert?

James Lovell: We might not technically qualify as a food desert because there is a PCC Community Markets at 4th and Union that is probably less than a mile away. And PCC has done as well as anyone could have: They have invited us to partner with them, and they gave some gift cards to our residents when we first opened. But the reality is that, long term, this is effectively a food desert, because our folks are not going to go into PCC unless they have a gift card, and even then, they’re not going to feel like they’re going to get what they need. It isn’t what I would call the first place I would send folks who have lived on the streets for a long time. Similarly, we’re just three blocks from Uwajimaya and several Asian grocery stores in the area. But I would still call this a food desert, because our folks aren’t going to find ingredients that they need to easily cook for themselves.

United Way of King County: What are ways you address those needs?

James Lovell: Our case managers and workers do grocery runs for our residents. But it’s not as challenging for day-to-day needs because our kitchen in the cafeteria can do hundreds of meals a day. We serve two meals a day seven days a week. Our staff gets in there at 6 a.m. and they start cooking and they don’t stop until the last dishes are in the sterilizer at 2 p.m. That’s always been a staple of Chief Seattle Club, food security, and now that we have residents it has expanded to be food security for them as well.

Chief Seattle Club is a member of United Way’s Indigenous Communities Fund, which was launched in 2020 to address the differential impact that the COVID-19 has had on communities of color. United Way thanks Brighton Jones for its sponsorship of the Indigenous Communities Fund.

United Way of King County: What types of food do you serve?

James Lovell: Each part of our café is an Indigenous highlight. A large part of the café is about normalizing Indigenous food, making sure that that part of our culture and identity isn’t seen as a gimmick or one-time thing. And we have Indigenous food days where we will have a wild rice stuffing with turkey or bison or elk stew, all things that hit that real highlight part.

James Lovell (continued): But what you cannot do under any circumstances is have food that doesn’t nourish people. Many folks on the street, what they are looking for is your basic spaghetti and sauce because that is comfort food for them. We’re not going to always go with the organic, homegrown potatoes. We’re trying to get at least 2,000 calories in people’s bodies through breakfast and lunch. We don’t do dinners, so this might be their last meal at 1 p.m.; they might not have another bite of food until 7 a.m. when they come in the next day. So, we do spaghetti and hamburgers and sandwiches. And we have snacks at the center between meals.

United Way of King County: How do you address dietary concerns?

James Lovell: We have to recognize dietary realities for a lot of folks, and a lot of those dietary realities begin in your mouth, where your diet is limited to what you can chew. A lot of folks on the folks don’t have dental care access, so we have to do softer food. Our members didn’t create the system that makes their diets as limited as they are but those are some of the limitations we have with our work.

Make a gift to feed a neighbor now. Click here.

Comments