Black Community Building Collective: Land, Trust

The Black Community Building Collective is a coalition of 15 Black-led organizations brought together by United Way of King County to build relationships, form strategies that impact the Black community, and implement those strategies with United Way funding that cedes decision-making power to communities. The Collective launched in 2020 to invest $3 million in local, Black-led organizations. We’ve invested an additional $1.5 million in 2022 and we anticipate more funding in later years.

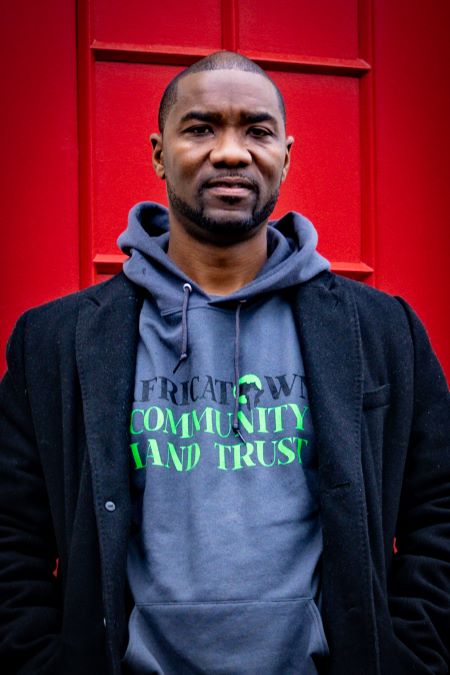

United Way features monthly spotlights of Collective members. This month, we’re spotlighting Africatown Community Land Trust (ACLT) an organization founded in 2016 that works for community land ownership in Seattle’s Central District to support the cultural and economic thriving of people that comprise the African diaspora in the greater Seattle region. We chatted with ACLT president and CEO Wyking Garrett and director of IT Evan Poncelet to learn more.

United Way of King County: What are the origins of Africatown Community Land Trust?

Wyking Garrett: Africatown Community Land Trust was founded in 2016 as part of the larger Africatown Asset Based Community Development initiative. The land trust was formed specifically to acquire, develop and steward land, while preserving and empowering the Black diaspora community in Greater Seattle. It really is an evolution of many years of work to build the Black community in Seattle, which obviously has rapidly been diminished and displaced. Our goal is about holding space and making space for our community to become a growing and thriving place. ALCT is about being a vehicle for the beauty, brilliance and best of the Black experience and African diaspora in the Central District, Seattle and beyond.

Is there any reference to the Africatown of Mobile, AL, which was established by formerly enslaved Blacks who in 1860 were the last slaves brought to the US during the Transatlantic Slave Trade?

Wyking Garrett: Originally, the concept of Africatown Community Land Trust is analogous to Chinatown, in observing that anywhere there is a community of Chinese outside of China it’s considered Chinatown and there is a direct correlation culturally to their mother country and heritage. The U.S. is pretty much the same: You have New England, New Orleans, New Hampshire—direct connection back to mother countries of [Europeans]. The spaces we occupy, the neighborhood, the places—and there wasn’t a direct correlation because there was intentional separation of people of African descent from their lands of origin.

But doing research, we learned about the very powerful story of Africatown in Mobile, AL, which is definitely an important Black story, American story and world history. We are connected now: We found each other. I’ve been there, and we’ve had representatives from there here as a part of our Imagine Africatown Design Weekend. I’m a juror on the Africatown Mobile International Design competition. We are definitely in a relationship and inspiring each other.

United Way of King County: Talk a bit about your background.

Wyking Garrett: I’m a third-generation community builder from the Central District. My grandfather was one of the co-founders of the Liberty Bank building. So, building institutions have been in my family; my father was a founder of the Northwest African American Museum, the Colman School and initiating a lot of different programs in the community around advancing Black community interests. I grew up on the front lines, as my father would call it, OJT—on the job training. I’ve been interning since I was about four years old. I graduated from Garfield High School. I left to go to school on the East Coast, came back and chose to make my own investments in the future of the community.

United Way of King County: What are some of the programs and offerings at ACLT?

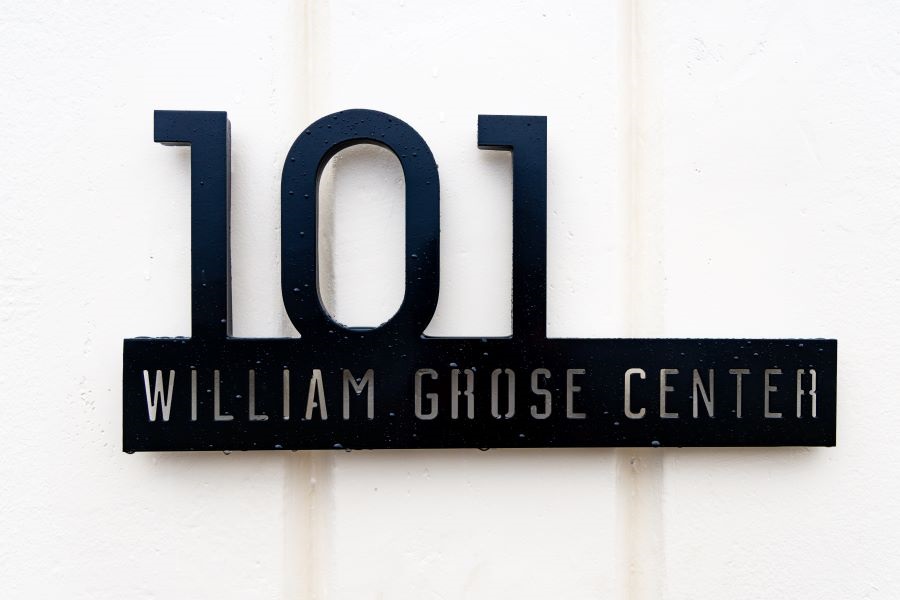

Wyking Garrett: At our initial core, ACLT is about community, real estate and economic development. But we also know that buildings don’t build community, people do. We also have to account for the people, their experiences, how they’ve been harmed throughout this time. Over the last year, we have expanded in programs and services, providing resident support services and community building at the Liberty Bank building. We provided support for businesses during the pandemic. And a year ago, with the acquisition of the 16th and Yesler block, we initiated the Benu Community Home. It is an enhanced shelter program focused on reducing the overrepresentation of Black men in the houseless population through culturally responsive, trauma-informed care model. And with us getting control of the former Fire Station Six, you have the William Grose Center for Cultural Innovation and Enterprise being launched. We just cut the ribbon in September.

United Way of King County: Talk about the William Grose Center.

Wyking Garrett: Initially the East Precinct was to be sited at 23rd and Yesler, and my father and the late [community activist and advocate] Isaiah Edwards led the effort to say that we don’t need a police station that responds after there is a victim and after there is damage, hurt and pain in the community. We need a positive institution to connect our young people to positive legacies, identities and the ability to develop their gifts and potential. That’s where the struggle of the African American Heritage Museum and Culture Center began before it went to the Colman School. So, the William Grose Center, opened 41 years later, fulfills that on that particular corner: the desire for a positive cultural institution that focuses on developing the talents and gifts of the community

Evan Poncelet: My main passion is to build the William Grose innovation hub for economic development. To that effect, I’ve been working with different partners in the community to have passion for different technologies that are going to be important and impactful to the economic futures for people in our community and building strong programs around that. This summer, we built some programs for youth, including a Makerspace program in partnership with the Billodue Makerspace at Seattle University to teach literacy. In the same way that books were once the currency of literacy all the way up the 20th century, we now have all these new technological marvels and there are opportunities to teach kids about 3-D printers and laser cutters to teach them how to be literate and authors of their environment.

We also had a Hackathon with the Blacks at Microsoft summer intern experience; we had 20 interns at Microsoft from all educational levels, studying artificial intelligence. We had some answers to some tough questions, including how do we amplify Black culture in historically Black neighborhoods, and can we build an app around that? And we had a program toward teaching youth Python coding, with 20 Ph.D. candidates from the University of Washington teaching youth as young as eight years old Python programming.

United Way of King County: Where do you want ACLT to be 10 years from now?

Wyking Garrett: I would like [that], within 10 years, we would have crystalized a future for the Black community in Seattle, a community that can be thriving and a part of the economic prosperity of this region. That means we have space, land, institutions, businesses, home ownership, vibrant arts and culture, and healthy folks—we want to be on a trajectory toward that. All of that won’t be achieved in 10 years, but all that is to be will be set in motion during the next ten years.

Comments